More than a dozen underwater robotic vehicles called “gliders” will be launched simultaneously this month in a massive, cooperative project involving 10 east coast research institutions, including the University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography. Dubbed Gliderpalooza 2013, the fleet of gliders will cruise the waters of the east coast for several weeks, collecting data that could help improve future hurricane forecasts.

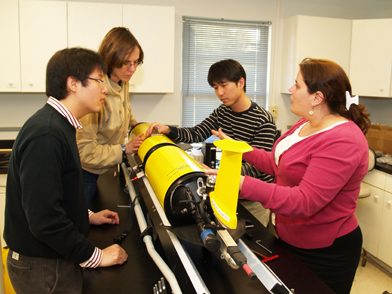

UGA Skidaway Institute scientist Catherine Edwards makes adjustments to the glider “Modena” while R/V Savannah crewman Mickey Baxley assists.

The gliders are torpedo-shaped vehicles, equipped with sensors and recorders to collect observations under all conditions. These autonomous underwater vehicles, or AUVs, move through the water by adjusting their buoyancy and pitch. Because they are highly energy efficient, gliders can remain on a mission for weeks at a time. Every 4 to 6 hours over their mission, they surface, report their data by satellite phone and receive instructions as needed.

According to Skidaway Institute scientist Catherine Edwards, one goal of Gliderpalooza 2013 is to test the feasibility of using a fleet of gliders to work together and to integrate their data—collected in the same time period, but over a wide geographical range.

“Gliders are powerful tools for oceanographers,” Edwards said. “We believe there is great potential to expand the value of them by working together on the deployments and integrating the data each collects.”

Another reason for promoting the use of gliders is their relatively inexpensive cost of operation. Gliders can operate for weeks at a time and in all kinds of weather conditions for a small fraction of the daily coast of an ocean-going research vessel.

“Gliders will never replace ships in oceanography—ship surveys are often the best way to collect data,” Edwards said. “But AUVs require far fewer resources and personnel than shipboard work, and can operate in conditions that would be impossible for traditional ship surveys. For lengthy data-collection missions, a glider can operate for pennies on the dollar by comparison.”

Scientists at Rutgers University are coordinating the project. Computers there will gather the data from the various glider groups, and make it available through a data assembly center for access to and visualization of the data in real time. Glider groups participating in Gliderpalooza will contribute pictures, updates and other notes of interest to scientists and the general public on a blog available at http://maracoos.org/blogs/main/.

September was chosen as the month for deployment because many important fish species migrate in that month, and a coordinated experiment can provide a more complete picture of oceanographic conditions and fish populations. September is the most active month for hurricanes, and there is interest in the use of gliders to better understand the effects of major storms on the mixing and transport of heat, nutrients and material.

The Skidaway Institute glider, nicknamed “Modena,” and several others will also be equipped with a special instrument to monitor fish migration. In order to track fish migration, some fisheries biologists tag fish with an acoustic transmitter. The tag-transmitter sends out a sound signal identifying the fish. Typically, receivers on buoys and other stationary platforms monitor these signals. This will be the first time a fleet of moving gliders will be used to monitor fish migration.

Gliderpalooza will also serve as a field test of a new glider navigation system developed by Georgia Tech graduate students, Dongsik Chang, Klimka Szwaykowska and Sungjin Cho, who are supervised by Edwards and Georgia Tech collaborator Fumin Zhang.

Gliders can only receive GPS information at the surface. They navigate underwater by dead reckoning, using information on ocean currents from the last leg of their mission. However, the strong tidal currents on the Georgia shelf, combined with the fast-moving Gulf Stream at the shelf edge often exceed a glider’s forward speed. This creates the opportunity for significant navigational errors.

The Glider Environmental Network Information System (GENIoS) is an automated system that optimizes glider navigation based on real time data from ocean models, high frequency radar and measurements from the glider itself. By integrating these data with ocean models, GENIoS provides a more accurate prediction of the currents the glider will navigate through, and chooses the most efficient target waypoints for the glider to aim for as those currents change in space and time.

During Gliderpalooza, the Skidaway Institute glider will conduct a triangle-shaped mission that includes one leg along the edge of the continental shelf, which also corresponds roughly to the western edge of the Gulf Stream.

“The combination of strong tidal currents and the influence of the Gulf Stream will serve as a strong test of the system,” Edwards said.

The collected glider data will go through NOAA’s National Data Buoy Center to the National Weather Service, the U.S. Navy and other data users for modeling. Data from the glider missions will also be public and available on the Integrated Ocean Observing System Glider Asset Map and at www.ndbc.noaa.gov/gliders.pahp.

Funding for Modena’s mission is provided by the UGA Skidaway Institute of Oceanography and the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association.

More information and an ongoing update on the progress of the project are available on the Gliderpalooza 2013 blog at http://maracoos.org/blogs/main/?p=448.