The University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography entered the fourth year of its black gill research program with a daylong cruise on board the Research Vessel Savannah and the introduction of a new smartphone app that will allow shrimpers to help scientists collect data on the problem.

Led by UGA scientists Marc Frischer, Richard Lee, Kyle Johnsen and Jeb Byers, the black gill study is being conducted in partnership with UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, and is funded by Georgia Sea Grant.

Black gill is a condition Georgia shrimpers first noticed in the mid-1990s. Many shrimpers have blamed black gill for poor shrimp harvests in recent years, but until Frischer began his study, almost nothing was known about the condition. Now the researchers know black gill is caused by a parasite—a single-cell animal called a ciliate—although the exact type of ciliate is still a mystery.

The October cruise had three goals. The first was simply to collect data and live shrimp for additional experiments.

“We were able to collect enough live shrimp in good shape to set up our next experiment,” Frischer said. “We are planning on running another direct mortality study to investigate the relationship between temperature and black gill mortality. This time, instead of comparing ambient temperature to cooler temperatures as we did last spring and summer, we will investigate the effects of warming.”

Researchers Marc Frischer (UGA Skidaway Institute), Brian Fluech and Lisa Gentit (both UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant) examine shrimp for signs of black gill.

If his hypothesis is correct, Frischer believes researchers would expect that raising fall water temperatures to warmer summer levels in a laboratory setting will induce black gill associated mortality in the shrimp caught in the fall.

Those studies will be compared to those that are being conducted in South Carolina in a slightly different manner. Frischer expects the results should be similar.

“However, as it goes with research, we are expecting surprises,” Frischer continued. “We also collected a good set of samples that will contribute to our understanding of the distribution and impact of black gill.”

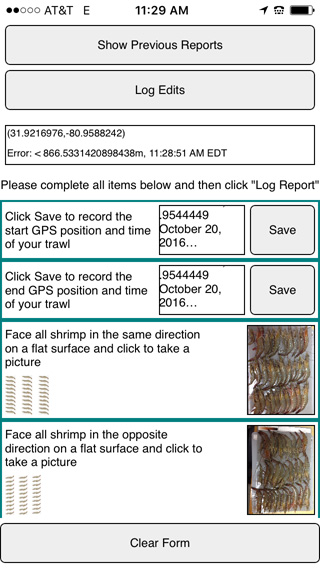

A second goal was to introduce and begin field testing a new smartphone application developed by Johnsen. The app is intended to be a tool that will allow shrimp boat captains and recreational shrimpers to assist the researchers by filling some of the holes in the data by documenting the extent of black gill throughout the shrimp season. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources conducts surveys of the shrimp population up and down the coast throughout the year. However, those surveys do not provide the researchers with the rich data set they need to really get an accurate assessment of the black gill problem.

A sample screen shot of the black gill smartphone application.

“Instead of having just one boat surveying the prevalence of black gill, imagine if we had a dozen, or 50 or a hundred boats all working with us,” Frischer said. “That’s the idea behind this app.”

The fishermen will use the app to document their trawls and report their data to a central database. Using GPS and the camera on their smartphone, they will record the location and images of the shrimp catch, allowing the researchers to see what the shrimpers see. If repeated by many shrimpers throughout the shrimping season, the information would give scientists a much more detailed picture of the prevalence and distribution of black gill.

“The app is complete and available on the app store, but we are still in the testing stages,” Johnsen said. “We want to make sure that it will be robust and as easy to use on a ship as possible before widely deploying it.”

Recruiting, training and coordinating the shrimpers will be the responsibility of UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant.

“I think it should be entirely possible to at least have a small group of captains comfortable and ready to start using it when the 2017 season begins,” Frischer said.

Johnsen is excited about the app for what it can provide to the shrimping and research community, but also the implications it has for using apps to involve communities in general.

“There is still work to be done to improve the usability of these systems,” he said. “But I’m confident that we are going to see an increasing number of these ‘citizen science’ applications going forward.”

The final aim of the cruise was to bring together diverse stakeholders, including fishery managers, shrimpers and scientists, to spend the day together and share ideas.

“This was a good venue for promoting cross-talk among the stakeholder groups,” Frischer said. “I had many good conversations and appreciated the opportunity to provide a few more research updates.”

Georgia DNR’s Pat Geer sorts through the marine life caught in a trawl net.

Frischer says he thinks the communication and cooperation among the various stakeholder groups has improved dramatically since the beginning of the study. He recalled that when the study began in 2013, tensions were high. Shrimpers were angry and demanded that something be done to address the problem of black gill. Meanwhile, fishery managers were unclear if black gill was even causing a problem and frustrated that no one could provide them any reliable scientific advice. The research community had not been engaged and given the resources to pursue valid investigations.

“In 2016, we still have black gill. The fishery is still in trouble, but it does feel like we are at least understanding a bit more about the issue,” Frischer said. “Most importantly, it is clear that all of us are now working together.

“My feeling is that the opportunity for us to spend a day like that together helps promote understanding, communication and trust among the shrimpers, managers and researchers.”