The ocean off the coast of North Carolina has a complex system of ocean currents that make it one of the least understood areas on the U.S. Eastern Seaboard. University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography professor Dana Savidge is leading a team of scientists, including UGA Skidaway Institute scientist Catherine Edwards, working to unravel the mysteries of the complex ocean currents near Cape Hatteras.

UGA Skidaway Institute scientists Dana Savidge (l) and Catherine Edwards

The four-year project, informally called PEACH: Processes driving Exchange At Cape Hatteras, was launched in early 2016 and is funded by a $5 million grant from the National Science Foundation to better understand the relationship between the waters of the continental shelf and the deep ocean.

“The U.S. continent, like others, has a shallow ocean immediately around it, called the continental shelf. It’s like an apron that extends out from the shoreline and it is fairly shallow, only about 60 meters deep,” Savidge said. “At its outer edge, the bottom drops sharply into the deep ocean, which can be miles deep.”

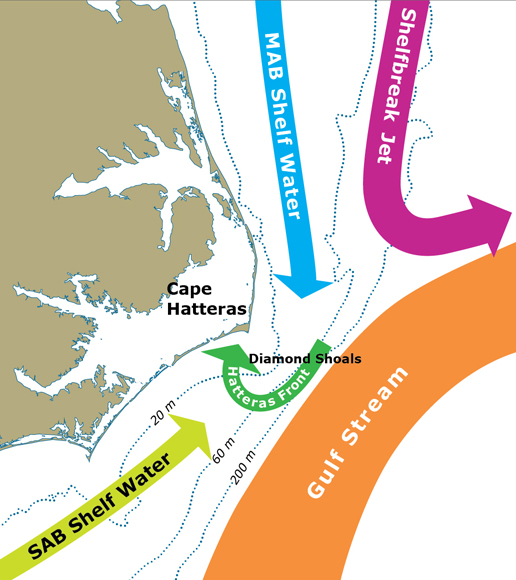

A diagram showing some of the complex currents at Cape Hatteras.

Exchange at the shelf edge can push cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean onto the shelf, which drives productivity of marine algae and the food web that it supports.

“There’s a reason people love offshore fishing at the edge of the Gulf Stream,” said Edwards. “Areas with regular exchange of shelf and deep waters are often known hotspots for commercial and recreational fishing.”

One reason Cape Hatteras attracted the researchers’ attention is that two opposing deep ocean currents collide there, making the ocean there highly dynamic. The warm Gulf Stream hugs the edge of the continental shelf as it flows north from the tip of Florida. At Cape Hatteras, the Gulf Stream opposes a colder current, the Slope Sea Gyre current, that moves southward along the mid-Atlantic coast. There the Gulfstream breaks away from the coast toward northern Europe.

There is a convergence of shelf currents at Cape Hatteras as well, as cool shelf waters of the mid-Atlantic continental shelf meet the warm salty shelf waters from the south. Each of these currents, on the shelf and at the shelf edge, has a distinct temperature, salinity and often a biological signal that reflects the origin of the water it carries. The team will measure these properties and ocean currents to better understand the exchange processes.

During the first year of the study, the researchers prepared and installed a network of sophisticated, high-tech instruments on the shore and in the ocean to monitor and capture the movement of water and changing properties like temperature and salinity. Together with scientists from the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, the team has worked with ocean models to better understand the interaction between shelf currents and the deeper currents of the Gulf Stream and the Slope Sea Gyre.

“Circulation on the continental shelf and the deep ocean can be quite separate things, but their effects on one another can be quite complicated,” Savidge said.

In addition to subsurface packages moored on the sea floor, the PEACH team is taking advantage of modern sampling techniques with shore-based radar systems and autonomous underwater vehicles called gliders to collect data remotely. Savidge’s hardware contribution to the project is a series of low-power, high-frequency radar stations that scan the waters of the continental shelf and measure the speed and direction of surface currents.

Dana Savidge works on a radar antenna on the Outer Banks.

“Measuring surface currents remotely with the radars is a real advantage here,” Savidge said. “They cover regions that are too shallow for mobile vehicles like ships to operate, while providing detailed information over areas where circulation can change quite dramatically over short times and distances.”

Savidge’s research technician, Gabe Matthias, installed the radar systems on the beach at Salvo and Buxton, and at the airports at Frisco and Ocracoke, North Carolina. Currently, the researchers are working out the bugs in the system and getting the four stations to work together to paint a composite picture of the surface currents. The radars produce a massive amount of data to be processed.

Edwards leads the effort to use gliders that will operate on the shelf for nearly the entire 16-month experiment. Gliders are shaped like torpedoes and equipped with sensors to measure properties like temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen. They can be programmed to cruise the underwater environment for weeks at a time, surfacing at regular intervals to transmit its collected data via a satellite phone.

Edwards’s specialty is improving the way these gliders sample the coastal waters using information from models and real-time data streams, including surface currents from Savidge’s HF radar. Edwards and doctoral students Qiuyang Tao and Mengxue Hou, co-advised by Edwards and Fumin Zhang of Georgia Tech, have developed new systems that optimize the path of the gliders based on near real-time information about current patterns and how they are expected to change, making operations more efficient and allowing better data collection.

“The glider provides data that help explain how temperature, salinity, and density change in space and time underwater, and the HF radar provides high resolution maps of surface currents every 20 minutes,” said Edwards. “The two systems are highly complementary, and their combination provides an unprecedented view of when, where and why there is exchange between the shelf and deep ocean.”

According to Savidge, the study should produce a greater understanding of the forces at work at Cape Hatteras with implications across a wide range of interests from fisheries management to pollution control. Microscopic marine plants, known as phytoplankton, are a vital part of the marine ecosystem. Phytoplankton are the very base of the marine food web and they produce approximately half the oxygen in the atmosphere. In addition to tracking deep water inputs that support productivity on the shelf, Savidge said, it would is also be important to understand any processes that transport carbon-rich shelf water back to the deep ocean. When phytoplankton and the rest of the food web convert nutrients into their own biomass, water returned to the deep ocean can carry large quantities of organic carbon with it.

The knowledge gathered at Cape Hatteras will be applicable to other oceans around the world.

“Cape Hatteras is the ideal place to look at these processes that you are going to find elsewhere,” Savidge said. “You have a lot of energetic forcing and everything is concentrated in a very small space, with large variations over short distances. The idea is to understand the processes so you can model them effectively. If you can do that, you can anticipate how circulation on the shelf and exchanges with the deep ocean will respond to changes in the Gulf Stream or the wind over time.”

The project will run through March 2020. The other members of the research team are Harvey Seim and John Bane of the University of North Carolina; Ruoying He of North Carolina State University; and Robert Todd, Magdalena Andres and Glen Gawarkiewicz from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

Savidge expressed special appreciation to the National Park Service and the North Carolina Department of Transportation for providing sites for the radar installations, and the University of North Carolina’s Coastal Studies Institute for help in installing them.