A team of University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography scientists has received a 4-year, $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation to study how dust in the atmosphere is deposited in the ocean and how that affects chemical and biological process there.

The research team of Clifton Buck, Daniel Ohnemus and Christopher Marsay will focus their efforts on a patch of the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

“Our overall goal is to look at the aerosol loading and concentrations in the atmosphere, the rate that dust is deposited into the ocean and what happens to it once it is in the water column,” Buck said.

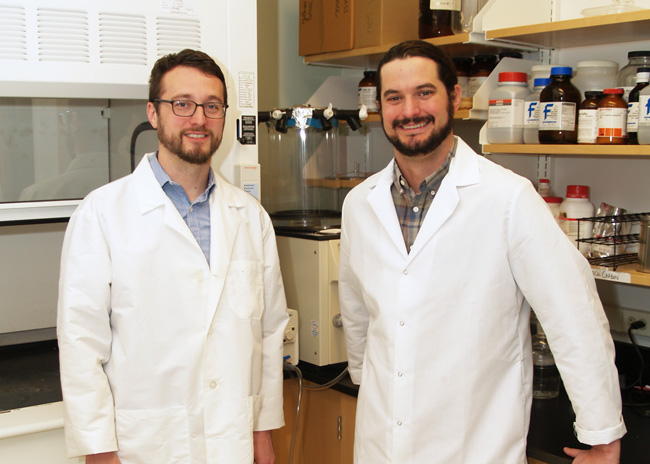

Daniel Ohnemus (l) and Clifton Buck

The chemistry of the ocean can be changed by the introduction and removal of elements, including trace elements which are present at low concentrations. In some cases, these elements are known to be vital to biological processes and ocean food webs. Near the shore, rivers are a large source for material from land to the ocean. Beyond the reach of rivers, and for most of the oceans, material blown from land through the air is the largest source of trace elements to surface waters.

“The ocean and the atmosphere are connected. What is in the atmosphere ends up in the ocean.” Ohnemus said. “Some part of what is in the ocean gets recycled back into the atmosphere, but mostly the movement is from the atmosphere to the ocean.”

The material enters the oceans dissolved in rain or by settling of dust particles. Understanding atmospheric sources of trace elements to the oceans is thus important to understanding both global chemical cycles and patterns of biological production. The team will look at trace metals like iron, which may appear in extremely low concentrations, but are essential to the growth of phytoplankton, the single-cell marine plants that serve as the base of the food web and produce approximately half the oxygen in the atmosphere. They will also look at other metals, like copper and cadmium, which are toxic and have a limiting influence on phytoplankton growth.

“Long-term atmospheric and ocean measurements are really hard to get at the same time in the same place, but that is what we are trying to do,” Ohnemus said.

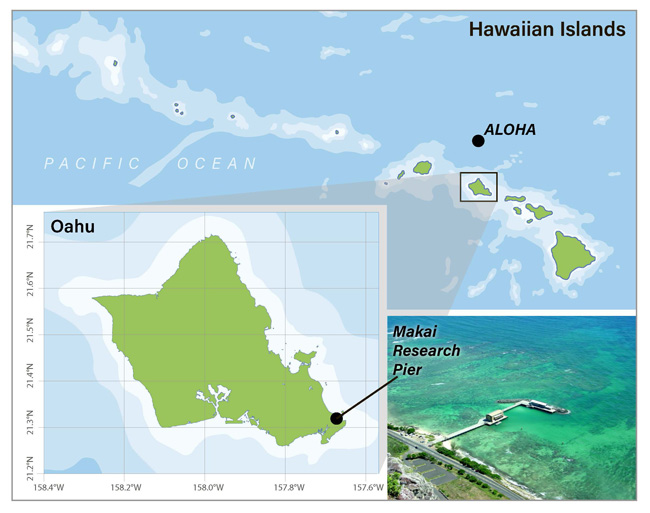

Beginning in early 2021, the team will begin collecting aerosol samples at the Makai Research Pier on the southeast or windward side of Oahu. They will also undertake the first of six cruises to collect water samples at a spot in the Pacific known as the Hawaii Ocean Time-Series Station Aloha. This is a six-mile wide section of ocean approximately 200 kilometers from Oahu where oceanographers from around the world study ocean conditions over long time spans.

This chart shows the locations of the research field sites. Credit: Lee Ann DeLeo

A key goal of this project will be to obtain relatively frequent measurements over two full annual cycles. By taking weekly aerosol samples and water samples every few months, the researchers hope to be able to obtain a picture of how the atmosphere and the ocean change on a weekly, monthly or seasonal basis.

“It is important to point out that the dust transport over the North Pacific has a distinct seasonal cycle,” Buck said. “Dust concentrations are going to be different during the winter than they are in the summer.”

In the past there have been studies of aerosol dust concentrations in that region, but they were conducted at the top of the Mauna Loa volcano.

“That’s almost 12 thousand feet up, and not necessarily representative of what is being deposited in the ocean,” Buck said. “That is the leap we are trying to make here.”

The researchers chose Hawaii as the site for their field work for several reasons. Hawaii offers direct access to the remote, nutrient-limited open ocean. Hawaii also has strong seasonal fluctuations to its aerosol inputs, meaning there should be measurable changes over the two-year time series. The Hawaii Ocean Time Series has conducted regular research cruises to Station ALOHA since the mid-1980s, so there is already a historic collection of relevant data. From a practical standpoint, it also means the scientists will have regular access to those cruises to collect their ocean samples.

Although this project will not focus on marine plants, those plants are the reason the scientists want to answer questions about the marine chemistry.

“A very small amount of aerosol dust from a desert in China can provide enough nutrients to satisfy plant growth for weeks,” Ohnemus said. “So it can have a huge influence on which algae will grow where and how successful they are.”

Working with contractors from Florida International University, the research team will use a radioisotope of beryllium to measure the rate of atmospheric deposition. Beryllium-7 is created only in the upper atmosphere by the exposure of nitrogen and oxygen to cosmic rays, and has a half-life of 53 days. By measuring the concentration of beryllium-7 in samples, they will be able to estimate the deposition rate at which beryllium and other materials are being deposited on the surface.

The team will also contract with scientists at the University of Hawaii to collect aerosol samples on a more frequent basis than the Georgia-based researchers would be able to do themselves.

The project is funded by NSF Grant #1949660 totaling $1,074,114.

One comment on “UGA Skidaway Institute scientists to study aerosol dust’s impact on life and chemistry in the ocean”