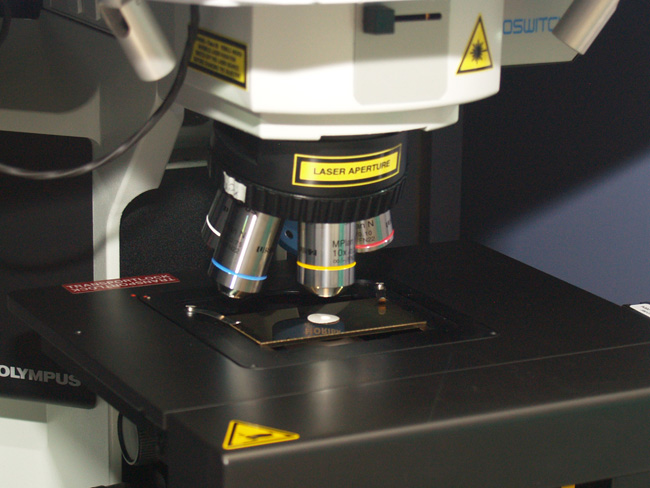

A new, high-tech microscope is giving scientists at the University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography a tool to study the tiniest particles and organisms in our environment in a whole new light.The Horiba Jobin Yvon XplorRA Plus Confocal Raman microscope uses lasers, rather than conventional light or a stream of electrons, to examine objects measuring smaller than a millionth of a meter or .04 thousandths of an inch.

“The way a Raman microscope works is fundamentally different from how conventional microscopes, such as those found in the classroom, operate,” UGA Skidaway Institute scientist Jay Brandes said. “With this instrument, a high energy laser beam is directed at the sample, and the instrument measures the light scattered back from it.”

UGA Skidaway Institute researcher Jay Brandes with the Raman microscope.

What distinguishes it even more from traditional microscopes is a phenomenon called the Raman effect. This was discovered in the 1930s by Indian physicist Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman. With the Raman microscope, some of the scattered light comes from interactions with the molecules in the sample, and these interactions leave a spectral “fingerprint” that can be isolated from the laser light and measured. Those “fingerprints” can tell scientists what the material is made of, whether it is natural organics like bacteria or detritus, inorganic minerals or plastics.

“Because it uses a high tech, automated microscope to perform these measurements, maps of sample composition and even three-dimensional maps are possible,” Brandes said.

The Raman microscope uses a laser to illuminate and analyze an object.

One immediate use for this instrument will be to study microplastic pollution in Georgia’s coastal environment. Brandes and a group of educators, students and volunteers, have been researching the microplastic pollution issue in coastal Georgia for several years. He says that locating and identifying microplastics in the environment or in an organism is difficult because of their tiny size.

“It’s not like it is a water bottle where you can look it and say ‘That’s plastic,’” Brandes said. “We see all kinds of microscopic particles, and, because they are so small and not always distinctively colored or shaped, it is difficult to distinguish microplastics from other substances.

“With this microscope, we will be able to look at a fiber and tell whether it is made of polyester, nylon, kevlar or whatever.”

A microfiber as seen by the Raman microscope.

Brandes and his team have been looking at the microplastics problem from several angles. They have taken hundreds of water samples along the Georgia coast, filtered the samples and analyzed the captured particles and fibers. The researchers also examine marine organisms, like fish and oysters, to see what organisms are consuming the microplastics and to what extent.

The instrument will allow sub-micron analysis of complex samples from a wide variety of other projects. It will be available to UGA Skidaway Institute scientists as well as other scientists from throughout the Southeast. In addition to benefitting researchers, the Raman microscope will enhance educational programs conducted at Skidaway Institute and the through the UGA Department of Marine Sciences. Once a set of standard methods and protocols have been established, it will also be available to support scientific research from institutions and organizations from around the Southeast.

The instrument was purchased with a $207,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.