UGA Skidaway Institute of Oceanography (SkIO) graduate student Mallory Mintz writes about her journey from the skyscrapers and subways of New York City to researching on the Georgia coast in a blog post originally published by UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant.

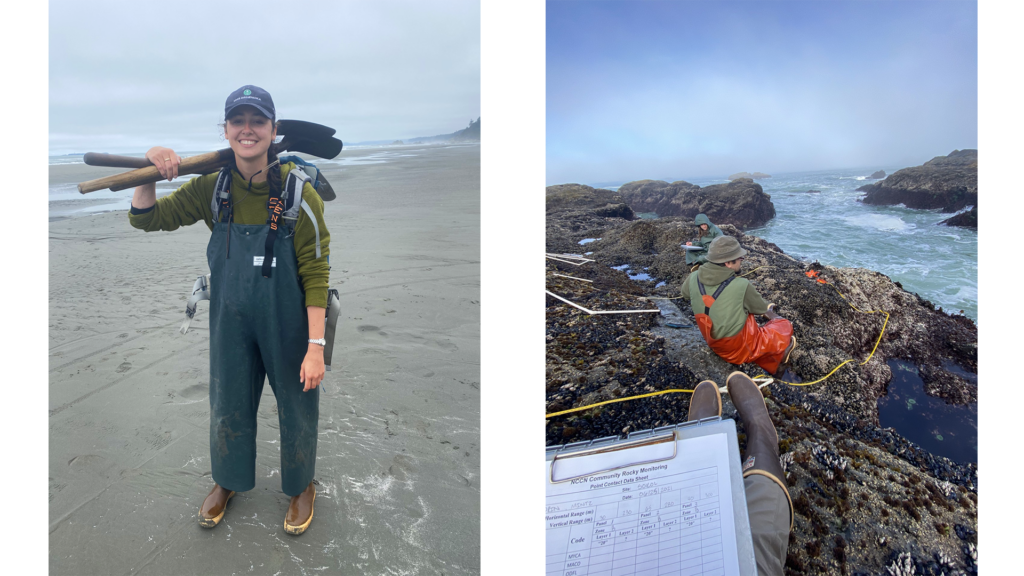

When the pandemic hit, I was living and working in New York City, but after a year of quarantines and new variants, I decided to leave the close quarters of the city behind. Armed with the latest vaccine, I traded subways and skyscrapers for the Pacific beaches of Forks, Washington, of Twilight fame. There, I joined the National Park Service, where I dove into hands-on ecological research. During my time at Olympic National Park, I served as a “guest scientist,” joining field research projects that spanned from marmot monitoring in the park’s alpine meadows to surveys of sea stars along its rocky shore. My role was to bridge the gap between complex, conservation-focused research happening in the park and the public’s understanding of it. During the day, I participated in fieldwork, and in the evenings, I gave campground amphitheater presentations to visitors. Through these experiences, I not only deepened my understanding of the science, but also found myself learning how to communicate nuanced ideas to a diverse audience.

One of the most eye-opening parts of my work involved identifying and monitoring marine life potentially affected by harmful algal blooms. Sometimes called “red tides” when dense populations of certain algae color water red, orange, or brown, harmful algal blooms can clog gills, deplete local dissolved oxygen, and release toxins. One such toxin, a neurotoxin called domoic acid, is produced by a species that occurs seasonally on the West Coast. Important shellfish fisheries on Washington’s outer coast have been largely closed for decades, in part because of the presence of domoic acid.

When small fish or other filter feeders graze on toxin-producing algae, domoic acid accumulates in their tissue. If sea otters and other animals—including humans— eat contaminated crab, fish, and shellfish, the accumulated toxin poisons them in turn. At high doses, domoic acid causes seizures, disorientation, and even death. Shellfish specialists like sea otters are especially vulnerable. Through the summer, I witnessed sea otters stranded on Washington beaches, potentially suffering from domoic acid toxicity. Seeing these effects firsthand motivated me to explore the environmental factors that drive harmful algal blooms, especially in areas with limited monitoring.

This interest brought me back across the country to Georgia’s Skidaway River Estuary, where I now study harmful algal blooms as Ph.D. student and Georgia Sea Grant Research Trainee, working with Assistant Professor Natalie Cohen. Our lab at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, part of UGA, investigates how environmental conditions influence gene expression in phytoplankton. My focus is on local blooms of a red tide species, Akashiwo sanguinea, which harms oyster health and can devastate larval recruitment. This work is important for predicting and mitigating the impacts of harmful algal blooms on coastal ecosystems and Georgia’s growing oyster aquaculture industry.

Beyond the lab, my days are punctuated by tide charts and weather forecasts, guiding year-round sampling from the Institute’s dock. I monitor phytoplankton communities to understand the changes in bloom-forming species, and the variable environmental conditions that precede them, like temperature, salinity, or nutrient availability. Long-term datasets allow us to identify patterns, and with real-time environmental monitoring, we can mitigate the damage caused by harmful algal blooms. For example, when densities of the oyster-killing species Akashiwo sanguinea are elevated, we warn the neighboring Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant Shellfish Research Lab to avoid sourcing water from our estuary for their hatchery operations.

I also collaborate with citizen scientists via the volunteer-led Phytoplankton Monitoring Network to detect harmful algal bloom events, empowering communities to safeguard their local waters.

I also collaborate with citizen scientists via the volunteer-led Phytoplankton Monitoring Network to detect harmful algal bloom events, empowering communities to safeguard their local waters.

As I reflect on my journey—from coast to coast and back again—I’m reminded of the ways that science and storytelling are deeply intertwined. Whether I’m sampling on the Skidaway River at sunrise or sifting through complex sequence data in the lab, my goal remains the same: to understand and communicate the forces shaping our coastal ecosystems. Looking ahead, I hope to continue bridging the gap between research and action, ensuring that the science of today informs the policies and conservation efforts of tomorrow.

One comment on “Student blog: Coast to coast, and back again”

Comments are closed.