The November cruise is officially complete for DolLAYER. We were able to go back to the sites where we saw the large bloom of diatoms earlier in the trip. We did not see the bloom anymore, and the gelatinous zooplankton were relatively sparse. Still, with all of the instruments working, we compiled a nice dataset that will be compared to the stratified season in the South Atlantic Bight (August 2024) and conditions in the northern Gulf of Mexico (August and November next year). Here is a picture of us recovering the modular Deep-focus Plankton Imager (mDPI) at night (photo credit Marc Frischer).

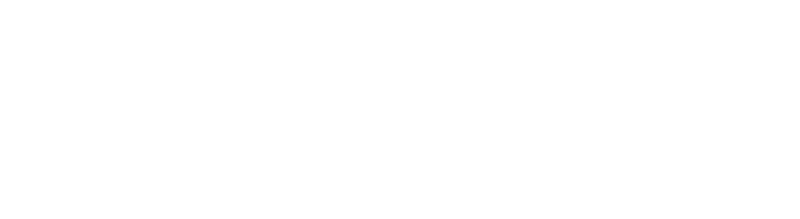

Our mDPI captured some exciting pictures of different zooplankton out there. Probably the most common large zooplankton we saw was the chaetognath (also known as an “arrow worm”). The name is derived from “chaeto” which means “bristle” and “gnath” which means “jaw.” This comes from the fact that the mouth of the chaetognath is surrounding by tiny venomous fangs that it uses to impale its prey. In our mDPI images, you cannot see the tiny fangs – they just show up as a black spot on the tip of the head.

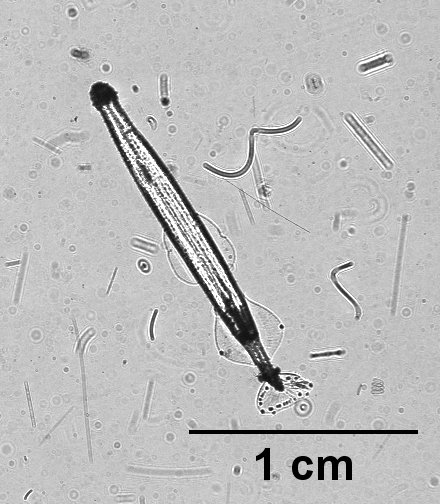

Here is a better look at what those “bristles” or fangs look like from an electron microscope pictured on the cover of the scientific journal “Current Biology.” Kind of scary – that might be the last thing that many zooplankton (such as copepods) see before they are gobbled up.

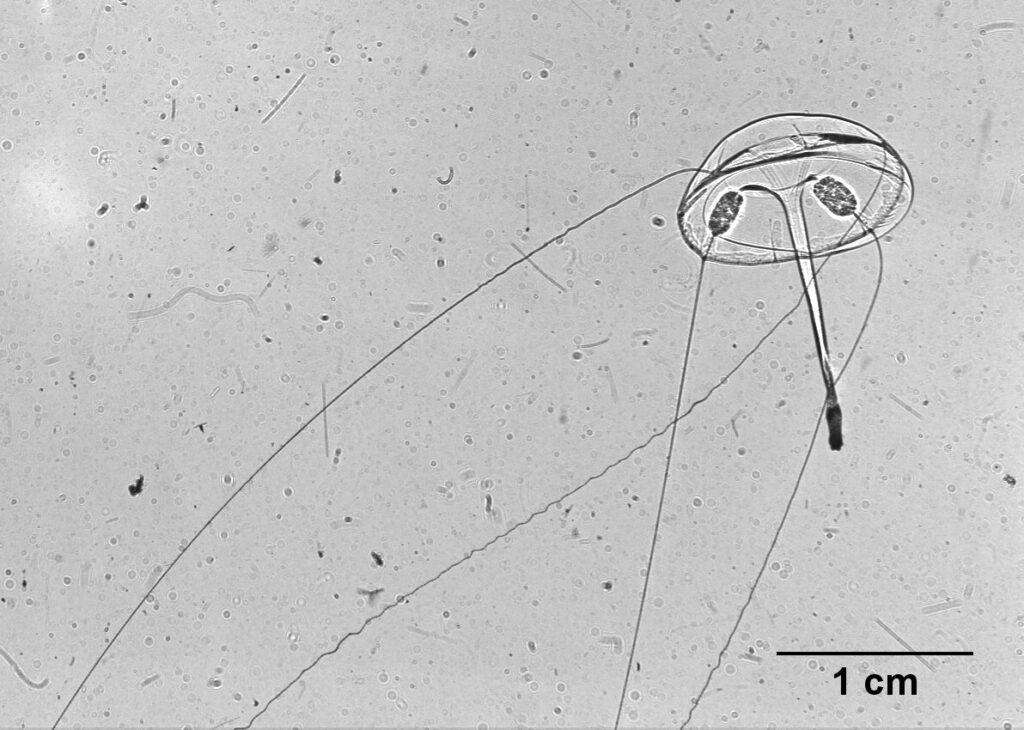

Although they were not common, we did see several types of gelatinous zooplankton. The one below is an example of a hydromedusa known as Liriope tetraphylla. Its scientific name comes from the fact that it has 4 tentacles (tetra = 4). The larger worm-like protrusion in the middle of the animal is its mouth. If a copepod or some other prey item gets ensnared in one of those 4 tentacles, the mouth can swoop over to consume it before the prey escapes. The 2 dark spots are the bell are the gonads, which look like they’re full of eggs. Perhaps this individual was about to spawn?

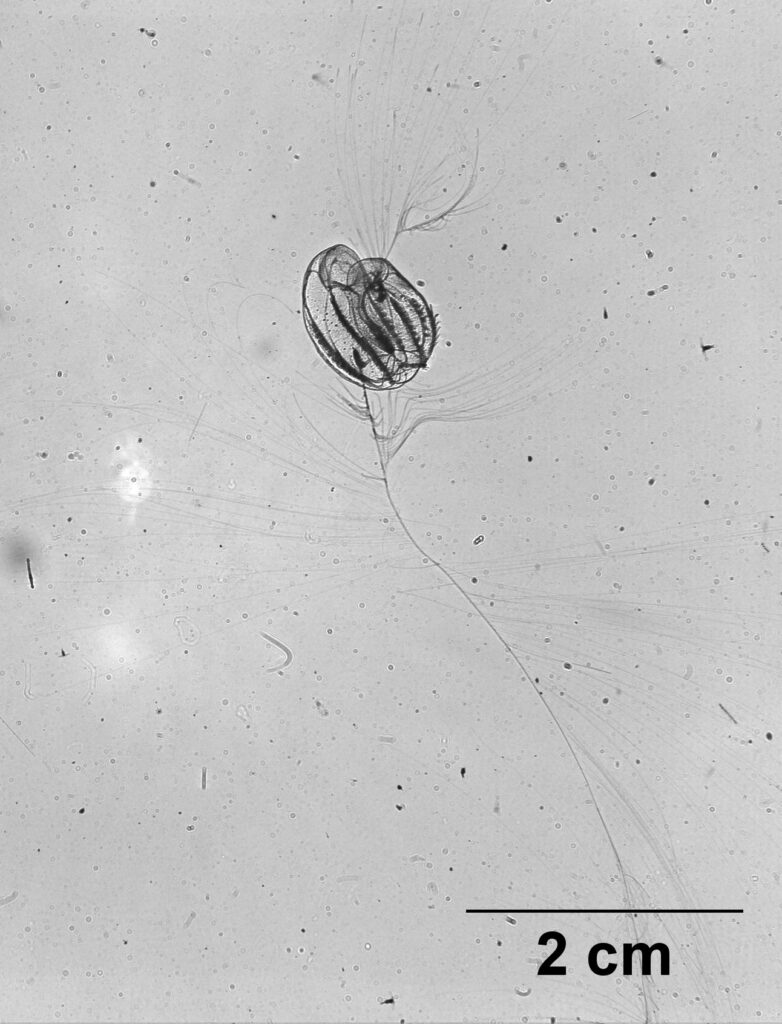

Here is a picture of a ctenophore that is likely the younger life stage of a lobate ctenophore, which I posted a picture of earlier. When the lobate ctenophores are young, they have these long tentacles that they eventually lose. This one is pretty big but still has its tentacles. Perhaps there are some conditions that are better for keeping the tentacles for a longer period of time? This one will eventually lose them and just have to rely on its 2 large lobes for feeding.

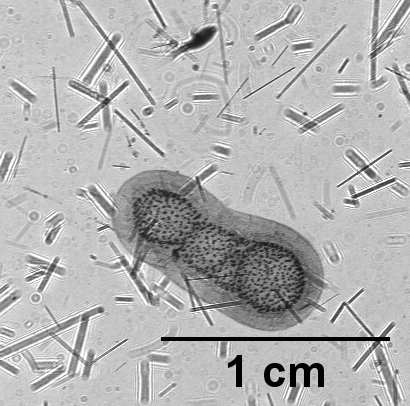

Grace in the ZERO-C lab is doing her Master’s work on radiolarians (and their associated zooplankton communities). We did not see many out there during November (radiolarians are generally more common in summer), but we found a nice picture of this colonial radiolarian known as “collodaria.” They consume other organisms and use their chloroplasts to perform photosynthesis. They look really beautiful in the images! This one is surrounded by diatom chains (which look like little sticks), and there is a copepod swimming above it with its antennae pulled inwards (probably trying to escape our imaging system).

And last but not least, we saw several larval fishes out there. One of the more common ones was the cusk eel (family Ophidiidae). This one has an appendicularian just above it – could that be a potential prey item? Our studies on the trophic position and the diets of these organisms should help us figure that out.

Even though we had some weather delays and rough seas at times, the cruise was a success. Now our team gets a little rest and recharges before digging into the data. Always great to go to sea with this science and ship crew on the RV Savannah!